Marie Courtault

K, f. 12 marts 1606

Senest redigeret=4 Maj 2007

Marie Courtault blev født 12 marts 1606 i Morville sur Seille, Meurthe et Moselle, Frankrig . Marie blev gift 17 september 1628 i Metz, Moselle, Frankrig

. Marie blev gift 17 september 1628 i Metz, Moselle, Frankrig , med David Xandry, søn af Jean Xandry og Susanne le Roy.

, med David Xandry, søn af Jean Xandry og Susanne le Roy.

. Marie blev gift 17 september 1628 i Metz, Moselle, Frankrig

. Marie blev gift 17 september 1628 i Metz, Moselle, Frankrig , med David Xandry, søn af Jean Xandry og Susanne le Roy.

, med David Xandry, søn af Jean Xandry og Susanne le Roy.Børn af Marie Courtault og David Xandry

- David Xandry

- Susanne Xandry+ f. 13 Feb 1632

- Isaac Xandry f. 2 Sep 1644, d. f 30 Maj 1724

Susanne Villaume

K, f. 25 december 1664, d. 2 juli 1739

Senest redigeret=5 Jan 2008

Susanne Villaume blev døbt 25 december 1664 i Metz, Moselle, Frankrig . Hun var datter af Jacques Villaume og Susanne Xandry. Susanne blev gift 24 januar 1697 i Buchholz, Niedersachsen, Tyskland

. Hun var datter af Jacques Villaume og Susanne Xandry. Susanne blev gift 24 januar 1697 i Buchholz, Niedersachsen, Tyskland , med Charles Bertrand. Susanne Villaume døde 2 juli 1739 i Strasbourg, Bas-Rhin, Frankrig

, med Charles Bertrand. Susanne Villaume døde 2 juli 1739 i Strasbourg, Bas-Rhin, Frankrig , i en alder af 74 år.

, i en alder af 74 år.

. Hun var datter af Jacques Villaume og Susanne Xandry. Susanne blev gift 24 januar 1697 i Buchholz, Niedersachsen, Tyskland

. Hun var datter af Jacques Villaume og Susanne Xandry. Susanne blev gift 24 januar 1697 i Buchholz, Niedersachsen, Tyskland , med Charles Bertrand. Susanne Villaume døde 2 juli 1739 i Strasbourg, Bas-Rhin, Frankrig

, med Charles Bertrand. Susanne Villaume døde 2 juli 1739 i Strasbourg, Bas-Rhin, Frankrig , i en alder af 74 år.

, i en alder af 74 år.| Far-Nat* | Jacques Villaume f. c 1633 |

| Mor-Nat* | Susanne Xandry f. 13 Feb 1632 |

Familie: Susanne Villaume og Charles Bertrand

Pierre Villaume

M, f. 31 juli 1667

Senest redigeret=26 Dec 2007

| Far-Nat* | Jacques Villaume f. c 1633 |

| Mor-Nat* | Susanne Xandry f. 13 Feb 1632 |

Marie Villaume

K, f. 24 december 1668

Senest redigeret=4 Maj 2007

Marie Villaume blev født 24 december 1668. Hun var datter af Jacques Villaume og Susanne Xandry. Marie Villaume blev døbt 26 december 1668. Marie blev gift cirka 1684 i Metz, Moselle, Frankrig , med Thomas le Poull.

, med Thomas le Poull.

, med Thomas le Poull.

, med Thomas le Poull.| Far-Nat* | Jacques Villaume f. c 1633 |

| Mor-Nat* | Susanne Xandry f. 13 Feb 1632 |

Familie: Marie Villaume og Thomas le Poull

Pierre Villaume

M, f. 29 august 1672

Senest redigeret=5 Jan 2008

Pierre Villaume blev født 29 august 1672. Han var søn af Jacques Villaume og Susanne Xandry. Pierre Villaume blev døbt 3 september 1672. Pierre blev gift 28 marts 1700 med Esther Philippe.

| Far-Nat* | Jacques Villaume f. c 1633 |

| Mor-Nat* | Susanne Xandry f. 13 Feb 1632 |

Familie: Pierre Villaume og Esther Philippe

Elisabeth Villaume

K, f. 12 september 1675

Senest redigeret=4 Maj 2007

Elisabeth Villaume blev født 12 september 1675. Hun var datter af Jacques Villaume og Susanne Xandry. Elisabeth Villaume blev døbt 15 september 1675.

| Far-Nat* | Jacques Villaume f. c 1633 |

| Mor-Nat* | Susanne Xandry f. 13 Feb 1632 |

Louis Villaume

M, f. 9 august 1678

Senest redigeret=5 Jan 2008

Louis Villaume blev født 9 august 1678. Han blev døbt 10 august 1678. Han var søn af Jacques Villaume og Susanne Xandry. Louis blev gift 21 juni 1701 med Sara Bachele.

| Far-Nat* | Jacques Villaume f. c 1633 |

| Mor-Nat* | Susanne Xandry f. 13 Feb 1632 |

Familie: Louis Villaume og Sara Bachele

Jean Xandry1

M, f. 1568, d. før 21 december 1636

Senest redigeret=27 Sep 2014

Jean Xandry blev døbt i 1568. Han var søn af Collas Xandry. Jean blev gift 2 maj 1593 i reformert kirke, Metz, Moselle, Frankrig , med Susanne le Roy, datter af Jean le Roy. Jean Xandry var i 1595 Vinbonde i Semècourt, Moselle, Frankrig

, med Susanne le Roy, datter af Jean le Roy. Jean Xandry var i 1595 Vinbonde i Semècourt, Moselle, Frankrig . Han døde før 21 december 1636.

. Han døde før 21 december 1636.

, med Susanne le Roy, datter af Jean le Roy. Jean Xandry var i 1595 Vinbonde i Semècourt, Moselle, Frankrig

, med Susanne le Roy, datter af Jean le Roy. Jean Xandry var i 1595 Vinbonde i Semècourt, Moselle, Frankrig . Han døde før 21 december 1636.

. Han døde før 21 december 1636.| Far-Nat* | Collas Xandry f. 1543 |

Børn af Jean Xandry og Susanne le Roy

- Elisabeth Xandry d. f 1668

- Susanne Xandry f. 1599, d. f 1606

- David Xandry+ f. 31 Maj 1600, d. f 1678

- Marie Xandry f. 11 Jun 1603

- Judith Xandry f. 1605

- Susanne Xandry f. 1606, d. c 1642

Kildehenvisninger

- [S163] Jean-Luc Renaud, online http://les.renaud.free.fr

Susanne le Roy

K, f. 27 januar 1566, d. 21 december 1630

Senest redigeret=4 Jun 2009

Susanne le Roy blev døbt 27 januar 1566 i Semècourt?, Moselle, Frankrig . Hun var datter af Jean le Roy. Susanne blev gift 2 maj 1593 i reformert kirke, Metz, Moselle, Frankrig

. Hun var datter af Jean le Roy. Susanne blev gift 2 maj 1593 i reformert kirke, Metz, Moselle, Frankrig , med Jean Xandry, søn af Collas Xandry. Susanne le Roy døde 21 december 1630 i Metz, Moselle, Frankrig

, med Jean Xandry, søn af Collas Xandry. Susanne le Roy døde 21 december 1630 i Metz, Moselle, Frankrig , i en alder af 64 år efter langvarig sygdom.

, i en alder af 64 år efter langvarig sygdom.

. Hun var datter af Jean le Roy. Susanne blev gift 2 maj 1593 i reformert kirke, Metz, Moselle, Frankrig

. Hun var datter af Jean le Roy. Susanne blev gift 2 maj 1593 i reformert kirke, Metz, Moselle, Frankrig , med Jean Xandry, søn af Collas Xandry. Susanne le Roy døde 21 december 1630 i Metz, Moselle, Frankrig

, med Jean Xandry, søn af Collas Xandry. Susanne le Roy døde 21 december 1630 i Metz, Moselle, Frankrig , i en alder af 64 år efter langvarig sygdom.

, i en alder af 64 år efter langvarig sygdom.| Far-Nat* | Jean le Roy f. 1540 |

Børn af Susanne le Roy og Jean Xandry

- Elisabeth Xandry d. f 1668

- Susanne Xandry f. 1599, d. f 1606

- David Xandry+ f. 31 Maj 1600, d. f 1678

- Marie Xandry f. 11 Jun 1603

- Judith Xandry f. 1605

- Susanne Xandry f. 1606, d. c 1642

Collas Xandry1

M, f. 1543

Senest redigeret=8 Nov 2007

Collas Xandry blev født i 1543 i Semècourt, Moselle, Frankrig . Han var søn af Didier Xandry og Anne Rozon.

. Han var søn af Didier Xandry og Anne Rozon.

. Han var søn af Didier Xandry og Anne Rozon.

. Han var søn af Didier Xandry og Anne Rozon.| Far-Nat* | Didier Xandry f. c 1515 |

| Mor-Nat* | Anne Rozon d. 14 Mar 1594 |

Barn af Collas Xandry

- Jean Xandry+ f. 1568, d. f 21 Dec 1636

Kildehenvisninger

- [S163] Jean-Luc Renaud, online http://les.renaud.free.fr

Pierre Luciatte1

M

Senest redigeret=12 Nov 2007

Pierre blev gift med Suzanne Gallois.

Barn af Pierre Luciatte og Suzanne Gallois

- Anne Luciatte f. 9 Mar 1668, d. f 19 Nov 1723

Kildehenvisninger

- [S164] Xandry stamtræ, online http://gw5.geneanet.org/txandry

Tobie Halanzy

M, f. 1 januar 1597

Senest redigeret=4 Maj 2007

Tobie Halanzy var vinbonde. Han blev født 1 januar 1597 i Jussy, Moselle, Frankrig . Tobie blev gift 18 januar 1626 med Marie Xandry, datter af Jean Xandry og Susanne le Roy.

. Tobie blev gift 18 januar 1626 med Marie Xandry, datter af Jean Xandry og Susanne le Roy.

. Tobie blev gift 18 januar 1626 med Marie Xandry, datter af Jean Xandry og Susanne le Roy.

. Tobie blev gift 18 januar 1626 med Marie Xandry, datter af Jean Xandry og Susanne le Roy.Familie: Tobie Halanzy og Marie Xandry

Elisabeth Xandry1

K, d. før 1668

Senest redigeret=25 Okt 2007

Elisabeth Xandry blev født i Semècourt, Moselle, Frankrig . Hun var datter af Jean Xandry og Susanne le Roy. Elisabeth Xandry blev døbt 8 marts 1598 i Metz, Moselle, Frankrig

. Hun var datter af Jean Xandry og Susanne le Roy. Elisabeth Xandry blev døbt 8 marts 1598 i Metz, Moselle, Frankrig . Elisabeth blev gift 14 april 1619 i Metz, Moselle

. Elisabeth blev gift 14 april 1619 i Metz, Moselle , med David Sept Sols, søn af Didier Sept Sols og Anne Martin. Elisabeth Xandry døde før 1668.

, med David Sept Sols, søn af Didier Sept Sols og Anne Martin. Elisabeth Xandry døde før 1668.

. Hun var datter af Jean Xandry og Susanne le Roy. Elisabeth Xandry blev døbt 8 marts 1598 i Metz, Moselle, Frankrig

. Hun var datter af Jean Xandry og Susanne le Roy. Elisabeth Xandry blev døbt 8 marts 1598 i Metz, Moselle, Frankrig . Elisabeth blev gift 14 april 1619 i Metz, Moselle

. Elisabeth blev gift 14 april 1619 i Metz, Moselle , med David Sept Sols, søn af Didier Sept Sols og Anne Martin. Elisabeth Xandry døde før 1668.

, med David Sept Sols, søn af Didier Sept Sols og Anne Martin. Elisabeth Xandry døde før 1668.| Far-Nat* | Jean Xandry f. 1568, d. f 21 Dec 1636 |

| Mor-Nat* | Susanne le Roy f. 27 Jan 1566, d. 21 Dec 1630 |

Familie: Elisabeth Xandry og David Sept Sols

Kildehenvisninger

- [S164] Xandry stamtræ, online http://gw5.geneanet.org/txandry

David Xandry

M

Senest redigeret=4 Maj 2007

David Xandry blev født i Semècourt, Moselle, Frankrig . Han var søn af David Xandry og Marie Courtault. David blev gift 23 januar 1661 i reformert kirke, Metz, Moselle, Frankrig

. Han var søn af David Xandry og Marie Courtault. David blev gift 23 januar 1661 i reformert kirke, Metz, Moselle, Frankrig , med Susanne la Walle.

, med Susanne la Walle.

. Han var søn af David Xandry og Marie Courtault. David blev gift 23 januar 1661 i reformert kirke, Metz, Moselle, Frankrig

. Han var søn af David Xandry og Marie Courtault. David blev gift 23 januar 1661 i reformert kirke, Metz, Moselle, Frankrig , med Susanne la Walle.

, med Susanne la Walle.| Far-Nat* | David Xandry f. 31 Maj 1600, d. f 1678 |

| Mor-Nat* | Marie Courtault f. 12 Mar 1606 |

Familie: David Xandry og Susanne la Walle

Isaac Xandry

M, f. 2 september 1644, d. før 30 maj 1724

Senest redigeret=4 Maj 2007

Isaac Xandry blev født 2 september 1644 i Metz, Moselle, Frankrig . Han var søn af David Xandry og Marie Courtault. Isaac blev gift 27 december 1665 i reformert kirke, Metz, Moselle, Frankrig

. Han var søn af David Xandry og Marie Courtault. Isaac blev gift 27 december 1665 i reformert kirke, Metz, Moselle, Frankrig , med Marie Willaume. Isaac blev gift 2 juni 1692 med Anne Luciatte, datter af Pierre Luciatte og Suzanne Gallois. Isaac Xandry døde før 30 maj 1724.

, med Marie Willaume. Isaac blev gift 2 juni 1692 med Anne Luciatte, datter af Pierre Luciatte og Suzanne Gallois. Isaac Xandry døde før 30 maj 1724.

. Han var søn af David Xandry og Marie Courtault. Isaac blev gift 27 december 1665 i reformert kirke, Metz, Moselle, Frankrig

. Han var søn af David Xandry og Marie Courtault. Isaac blev gift 27 december 1665 i reformert kirke, Metz, Moselle, Frankrig , med Marie Willaume. Isaac blev gift 2 juni 1692 med Anne Luciatte, datter af Pierre Luciatte og Suzanne Gallois. Isaac Xandry døde før 30 maj 1724.

, med Marie Willaume. Isaac blev gift 2 juni 1692 med Anne Luciatte, datter af Pierre Luciatte og Suzanne Gallois. Isaac Xandry døde før 30 maj 1724.| Far-Nat* | David Xandry f. 31 Maj 1600, d. f 1678 |

| Mor-Nat* | Marie Courtault f. 12 Mar 1606 |

Familie: Isaac Xandry og Marie Willaume

Familie: Isaac Xandry og Anne Luciatte

Susanne la Walle

K

Senest redigeret=20 Nov 2007

Susanne blev gift 23 januar 1661 i reformert kirke, Metz, Moselle, Frankrig , med David Xandry, søn af David Xandry og Marie Courtault.

, med David Xandry, søn af David Xandry og Marie Courtault.

, med David Xandry, søn af David Xandry og Marie Courtault.

, med David Xandry, søn af David Xandry og Marie Courtault.Familie: Susanne la Walle og David Xandry

Marie Willaume

K, d. før 1691

Senest redigeret=4 Maj 2007

Marie blev gift 27 december 1665 i reformert kirke, Metz, Moselle, Frankrig , med Isaac Xandry, søn af David Xandry og Marie Courtault. Marie Willaume døde før 1691.

, med Isaac Xandry, søn af David Xandry og Marie Courtault. Marie Willaume døde før 1691.

, med Isaac Xandry, søn af David Xandry og Marie Courtault. Marie Willaume døde før 1691.

, med Isaac Xandry, søn af David Xandry og Marie Courtault. Marie Willaume døde før 1691.Familie: Marie Willaume og Isaac Xandry

Anne Luciatte

K, f. 9 marts 1668, d. før 19 november 1723

Senest redigeret=4 Maj 2007

Anne Luciatte blev født 9 marts 1668 i Vantoux, Moselle, Frankrig . Hun var datter af Pierre Luciatte og Suzanne Gallois. Anne blev gift 2 juni 1692 med Isaac Xandry, søn af David Xandry og Marie Courtault. Anne Luciatte døde før 19 november 1723.

. Hun var datter af Pierre Luciatte og Suzanne Gallois. Anne blev gift 2 juni 1692 med Isaac Xandry, søn af David Xandry og Marie Courtault. Anne Luciatte døde før 19 november 1723.

. Hun var datter af Pierre Luciatte og Suzanne Gallois. Anne blev gift 2 juni 1692 med Isaac Xandry, søn af David Xandry og Marie Courtault. Anne Luciatte døde før 19 november 1723.

. Hun var datter af Pierre Luciatte og Suzanne Gallois. Anne blev gift 2 juni 1692 med Isaac Xandry, søn af David Xandry og Marie Courtault. Anne Luciatte døde før 19 november 1723.| Far-Nat* | Pierre Luciatte |

| Mor-Nat* | Suzanne Gallois f. 1642 |

Familie: Anne Luciatte og Isaac Xandry

Daniel Villaume

M, f. 17 marts 1710, d. 1710

Senest redigeret=2 Dec 2009

Oplysningerne stammer fra en afskrift af Daniel Villaumes egne optegnelser, opdateret af Charles Antoine Villaume, citeret efter Fredi Paludan Bentsen.

Daniel Villaume blev født 17 marts 1710 i Berlin, Tyskland . Han var søn af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot. Daniel Villaume blev døbt 19 marts 1710 i Berlin

. Han var søn af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot. Daniel Villaume blev døbt 19 marts 1710 i Berlin . Han døde i 1710.

. Han døde i 1710.

Daniel Villaume blev født 17 marts 1710 i Berlin, Tyskland

. Han var søn af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot. Daniel Villaume blev døbt 19 marts 1710 i Berlin

. Han var søn af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot. Daniel Villaume blev døbt 19 marts 1710 i Berlin . Han døde i 1710.

. Han døde i 1710.| Far-Nat* | Daniel Villaume f. 9 Sep 1684, d. 9 Jun 1741 |

| Mor-Nat* | Marie Paquot f. 1685, d. 3 Maj 1727 |

Louis Villaume

M, f. 28 maj 1711

Senest redigeret=5 Jan 2008

Louis Villaume blev født 28 maj 1711 i Berlin, Tyskland . Han blev døbt i Friedrichsstadt, Berlin, Tyskland

. Han blev døbt i Friedrichsstadt, Berlin, Tyskland . Han var søn af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot. Louis blev gift i 1740 i Berlin

. Han var søn af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot. Louis blev gift i 1740 i Berlin med Regine Kirch.

med Regine Kirch.

. Han blev døbt i Friedrichsstadt, Berlin, Tyskland

. Han blev døbt i Friedrichsstadt, Berlin, Tyskland . Han var søn af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot. Louis blev gift i 1740 i Berlin

. Han var søn af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot. Louis blev gift i 1740 i Berlin med Regine Kirch.

med Regine Kirch.| Far-Nat* | Daniel Villaume f. 9 Sep 1684, d. 9 Jun 1741 |

| Mor-Nat* | Marie Paquot f. 1685, d. 3 Maj 1727 |

Familie: Louis Villaume og Regine Kirch

Marie Villaume

K, f. 10 marts 1713

Senest redigeret=5 Jan 2008

Marie Villaume blev født 10 marts 1713 i Berlin, Tyskland . Hun var datter af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot. Marie Villaume blev døbt 14 marts 1713 i vom Werder, Berlin, Tyskland. Marie blev gift 12 november 1733 i Berlin

. Hun var datter af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot. Marie Villaume blev døbt 14 marts 1713 i vom Werder, Berlin, Tyskland. Marie blev gift 12 november 1733 i Berlin med Jean Nicolas Drovin.

med Jean Nicolas Drovin.

. Hun var datter af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot. Marie Villaume blev døbt 14 marts 1713 i vom Werder, Berlin, Tyskland. Marie blev gift 12 november 1733 i Berlin

. Hun var datter af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot. Marie Villaume blev døbt 14 marts 1713 i vom Werder, Berlin, Tyskland. Marie blev gift 12 november 1733 i Berlin med Jean Nicolas Drovin.

med Jean Nicolas Drovin.| Far-Nat* | Daniel Villaume f. 9 Sep 1684, d. 9 Jun 1741 |

| Mor-Nat* | Marie Paquot f. 1685, d. 3 Maj 1727 |

Familie: Marie Villaume og Jean Nicolas Drovin

Charlotte Villaume

K, f. 3 juni 1715

Senest redigeret=5 Jan 2008

Charlotte Villaume blev født 3 juni 1715 i Berlin, Tyskland . Hun var datter af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot. Charlotte Villaume blev døbt 10 juni 1715 i vom Werder, Berlin, Tyskland.

. Hun var datter af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot. Charlotte Villaume blev døbt 10 juni 1715 i vom Werder, Berlin, Tyskland.

. Hun var datter af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot. Charlotte Villaume blev døbt 10 juni 1715 i vom Werder, Berlin, Tyskland.

. Hun var datter af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot. Charlotte Villaume blev døbt 10 juni 1715 i vom Werder, Berlin, Tyskland.| Far-Nat* | Daniel Villaume f. 9 Sep 1684, d. 9 Jun 1741 |

| Mor-Nat* | Marie Paquot f. 1685, d. 3 Maj 1727 |

Madeleine Villaume

K, f. 30 april 1720

Senest redigeret=4 Maj 2007

Madeleine Villaume blev døbt i Neustadt Reformierte Kirche, Berlin, Tyskland. Hun blev født 30 april 1720 i Berlin, Tyskland . Hun var datter af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot.

. Hun var datter af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot.

. Hun var datter af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot.

. Hun var datter af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot.| Far-Nat* | Daniel Villaume f. 9 Sep 1684, d. 9 Jun 1741 |

| Mor-Nat* | Marie Paquot f. 1685, d. 3 Maj 1727 |

Charles Antoine Villaume

M, f. 1 november 1723, d. 1723

Senest redigeret=2 Dec 2009

Charles Antoine Villaume blev født 1 november 1723 i Stettin, Pommern, Tyskland . Han døde i 1723 Afskrift af Daniel Villaume's egne optegnelser, opdateret af Charles Antoine Villaume. Han var søn af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot.

. Han døde i 1723 Afskrift af Daniel Villaume's egne optegnelser, opdateret af Charles Antoine Villaume. Han var søn af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot.

. Han døde i 1723 Afskrift af Daniel Villaume's egne optegnelser, opdateret af Charles Antoine Villaume. Han var søn af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot.

. Han døde i 1723 Afskrift af Daniel Villaume's egne optegnelser, opdateret af Charles Antoine Villaume. Han var søn af Daniel Villaume og Marie Paquot.| Far-Nat* | Daniel Villaume f. 9 Sep 1684, d. 9 Jun 1741 |

| Mor-Nat* | Marie Paquot f. 1685, d. 3 Maj 1727 |

Sara Paris

K, f. cirka 1716

Senest redigeret=3 Jan 2008

Sara Paris blev født cirka 1716 i Angermünde, Uckermark, Brandenburg, Tyskland . Hun var datter af Jean Paris og Sara Couvreur. Sara blev gift cirka 1746 med Charles Marre, søn af Mathieu Marre og Anne Marie Guerrier.

. Hun var datter af Jean Paris og Sara Couvreur. Sara blev gift cirka 1746 med Charles Marre, søn af Mathieu Marre og Anne Marie Guerrier.

. Hun var datter af Jean Paris og Sara Couvreur. Sara blev gift cirka 1746 med Charles Marre, søn af Mathieu Marre og Anne Marie Guerrier.

. Hun var datter af Jean Paris og Sara Couvreur. Sara blev gift cirka 1746 med Charles Marre, søn af Mathieu Marre og Anne Marie Guerrier.| Far-Nat* | Jean Paris |

| Mor-Nat* | Sara Couvreur |

Børn af Sara Paris og Charles Marre

- Jean Marre f. 27 Okt 1746

- Marie Marre f. 27 Feb 1748, d. 4 Nov 1750

- Marianne Marre f. 17 Dec 1749, d. 16 Nov 1750

- Susanne Marre+ f. 25 Okt 1751, d. 9 Apr 1815

- Jaques Marre f. 26 Okt 1753, d. 11 Sep 1757

- Renée Marre f. 21 Sep 1755, d. 20 Sep 1757

- Jean Louis Marre f. 21 Jan 1758, d. 2 Jul 1758

- Louise Marre f. 8 Jan 1759, d. 9 Feb 1760

- Marie Anne Marre f. 9 Jan 1761

- Jean Louis Marre f. 14 Nov 1764

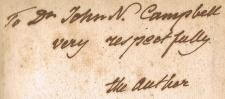

Henri Louis Villaume Ducoudray Holstein1,2,3

M, f. 23 september 1772, d. 23 april 1839

Ducoudray-Holstein fortæller i artiklen “Memoirs of my life. By an old soldier” om sin fødsel og opvækst:4

I was born in a chateau; my father was neither Monsieur le Baron de Tundertentronk, nor were the windows of his chateau without panes of glass. His large mansion had all the conveniences and brilliancy of the elegantest castles of the Duchy of H-.

The 23d of September, 17**, was a troublesome day for our family; my father had sent for the most famous physician from the capital, besides his own who resided with him, and attended the inhabitants of his vast domains. Both were destines to assist my entrance in this world “of sufferings and misery,” as my good grandmother exclaimed daily, with her twenty thousands a year, and living in splendour and luxury.

Some dozen old and young aunts, cousins and other relations, claiming anxiously the honor of their alliance since the fifteenth century, had assembled before the arrival of the doctor. My parents were often much amused with the manner in which the endeavoured to prove the degrees of their affinity with our family. Two powerful reasons excited in them this anxiety of relation: vanity and avarice. The former was flattered by the acknowledgment of that kindred, and as my father and mother possessed great wealth, these legions of dear cousins, and cousines, lived in the charitable hope, “that God might relieve my parents soon from this world of sin and misery, and not forget them in their will”! They, my cousins, had but a scanty six thousand a year, and thought themselves poor and miserable. What a pity!

Twenty-four hours had scarcely expired after my entrance in the world, when the evil spirit, etiquette, came to trouble the satisfaction of the house. My grandmamma, and the whole host of aunts and cousins, spoke of nothing else to my very weak and suffering mother, than “who should have the honor of being the godfather and godmother of a little baby,” twenty-four hours old! Each of them proposed her candidate, whom each one supported with great loquacity and noise, and sometimes the discussion became so warm and obstinate, that my mother entreated them in vain, to trouble her not at the present with such matters; she would settle this with my father at another time. They stopped for a while, but soon commenced again, in spite of all the urgent entreaties of my parents and the doctors. My father was at last obliged to recur to the following stratagem. He ordered secretly that various notes should be brought, addressed to the most troublesome of our visitors, by which the one received the news that her husband had broken an arm in falling from his horse at the hunt; the second that her friend, the countess R***, was dangerously ill, and requested her immediate presence; a third was expected home by her dear brother, just arrived from Italy, &c. The bustle was great, and the chateau soon cleared of all those loquacious females.

My father silenced all controversy, by inviting the reigning prince of Anhalt Dessau to be my godfather, and to choose himself the godmother. This prince was a friend of my father, one of those rare sovereigns who wished the happiness of their subjects; he governed and examined by himself and not through his ministers. He wrote a letter of excuse saying, that his duty going before his friendship and affection, he was unable to absent himself, but that he would send with his daughter the Gen. Count de Lottum, to represent him at the ceremony of christening.

My parents decided that I and my brother Charles, fifteen months older, should be educated together. The principles of my father differed vastly with those of his equals and of the then existing time, full of prejudices, vanity and ridiculous etiquette. A little boy for instance of four or five years old, whose parents were of high nobility, could never take a walk, except when accompanied by his tutor and two lackeys in full livery behind him. His hat was adorned with white small ostrich feathers, which covered its whole inside, and his coat full of golden laces; then, said they, it was highly necessary that the young count should not be confounded with the plebeians! His parents got him a company, a squadron, or the title of gentleman of the king’s bedchamber, (Kammeriunker).

It is a notorious fact, that in a kingdom in miniature like that of Denmark, of scarcely two millions of inhabitants, is to be found a greater number, a greater variety of titles, knights and soldiers, than in any other country of Europe. The army is about forty thousand men strong, besides the navy, and more than thirty thousand have titles, ribands, orders, or stars! In every society at Copenhagen, Schleswig, Kiel, &c., is to be found some dozen counsellors called justizrath, hofrath, etatsrath, educationsrath, comerzienrath, legationsrath, conferenzrath, or geheimerath, &c., who have never given any advice, or have been asked for by the king or his ministers. The majority of these titles and orders can be bought at a fixed price, and form a part of the revenue of the crown, like imports and exports of sugar and coffee, &c., in our custom houses. The government, glad to find fools enough to spend their money for banbles and toys, grants, graciously, the most humble request of these fools, and ridicules secretly these poor monkeys, an expression which I heard often from the then prince royal, now king of Denmark.

In spite of this general mania of titles, my father was one of the few, (among whom was also count Louis Reventlow,) who never applied neither for orders or titles. e was busily engaged to render his numerous peasantry as happy as possible, and was the first in the whole kingdom who gave them freedom and liberty; they were formerly slaves. But his greatest care was to give us a good, sound, and liberal education.

Ursula Acosta refererer hans fødselsregistrering fra Schwedt:5

Den 23. september 72 blev født i Schwedt kl. 8 om morgenen Henri Louis, søn af Pierre Villaume, præst i den franske kirke i Schwedt, og hans hustru Susanne, født Marre. Han blev hjemmedøbt den 8. oktober af sin far, båret af hans Kgl. Højhed markgreve Friedrich Heinrich von Schwedt und Wegern for hendes Kgl. højhed prinsesse Louise af Anhalt Dessau, født af Preussen.

Underskrevet: Villaume, præst

Friedrich Heinrich, prins af Preussen, markgrave af Schwedt (* 21 august 1709 i Schwedt, † 12 december 1788 i Schwedt) var den sidste ejer af det preussiske Sekundogenitur Schwedt-Wildenbruch.

Da hans bror Friedrich Wilhelm døde i 1771, arvede han herredømmet over Schwedt-Wildenbruch. Som markgrave af Brandenburg-Schwedt var han var en fortaler for kunst, især teater.

Luise af Brandenburg-Schwedt

L(o)uise Henriette Wilhelmine von Brandenburg-Schwedt (* 24. September 1750 i Stolzenberg, nu Rózanki /Polen; † 21. December 1811 i Dessau ) var gennem sit ægteskab prinsesse og senere hertuginde af Anhalt-Dessau.

I was born in a chateau; my father was neither Monsieur le Baron de Tundertentronk, nor were the windows of his chateau without panes of glass. His large mansion had all the conveniences and brilliancy of the elegantest castles of the Duchy of H-.

The 23d of September, 17**, was a troublesome day for our family; my father had sent for the most famous physician from the capital, besides his own who resided with him, and attended the inhabitants of his vast domains. Both were destines to assist my entrance in this world “of sufferings and misery,” as my good grandmother exclaimed daily, with her twenty thousands a year, and living in splendour and luxury.

Some dozen old and young aunts, cousins and other relations, claiming anxiously the honor of their alliance since the fifteenth century, had assembled before the arrival of the doctor. My parents were often much amused with the manner in which the endeavoured to prove the degrees of their affinity with our family. Two powerful reasons excited in them this anxiety of relation: vanity and avarice. The former was flattered by the acknowledgment of that kindred, and as my father and mother possessed great wealth, these legions of dear cousins, and cousines, lived in the charitable hope, “that God might relieve my parents soon from this world of sin and misery, and not forget them in their will”! They, my cousins, had but a scanty six thousand a year, and thought themselves poor and miserable. What a pity!

Twenty-four hours had scarcely expired after my entrance in the world, when the evil spirit, etiquette, came to trouble the satisfaction of the house. My grandmamma, and the whole host of aunts and cousins, spoke of nothing else to my very weak and suffering mother, than “who should have the honor of being the godfather and godmother of a little baby,” twenty-four hours old! Each of them proposed her candidate, whom each one supported with great loquacity and noise, and sometimes the discussion became so warm and obstinate, that my mother entreated them in vain, to trouble her not at the present with such matters; she would settle this with my father at another time. They stopped for a while, but soon commenced again, in spite of all the urgent entreaties of my parents and the doctors. My father was at last obliged to recur to the following stratagem. He ordered secretly that various notes should be brought, addressed to the most troublesome of our visitors, by which the one received the news that her husband had broken an arm in falling from his horse at the hunt; the second that her friend, the countess R***, was dangerously ill, and requested her immediate presence; a third was expected home by her dear brother, just arrived from Italy, &c. The bustle was great, and the chateau soon cleared of all those loquacious females.

My father silenced all controversy, by inviting the reigning prince of Anhalt Dessau to be my godfather, and to choose himself the godmother. This prince was a friend of my father, one of those rare sovereigns who wished the happiness of their subjects; he governed and examined by himself and not through his ministers. He wrote a letter of excuse saying, that his duty going before his friendship and affection, he was unable to absent himself, but that he would send with his daughter the Gen. Count de Lottum, to represent him at the ceremony of christening.

My parents decided that I and my brother Charles, fifteen months older, should be educated together. The principles of my father differed vastly with those of his equals and of the then existing time, full of prejudices, vanity and ridiculous etiquette. A little boy for instance of four or five years old, whose parents were of high nobility, could never take a walk, except when accompanied by his tutor and two lackeys in full livery behind him. His hat was adorned with white small ostrich feathers, which covered its whole inside, and his coat full of golden laces; then, said they, it was highly necessary that the young count should not be confounded with the plebeians! His parents got him a company, a squadron, or the title of gentleman of the king’s bedchamber, (Kammeriunker).

It is a notorious fact, that in a kingdom in miniature like that of Denmark, of scarcely two millions of inhabitants, is to be found a greater number, a greater variety of titles, knights and soldiers, than in any other country of Europe. The army is about forty thousand men strong, besides the navy, and more than thirty thousand have titles, ribands, orders, or stars! In every society at Copenhagen, Schleswig, Kiel, &c., is to be found some dozen counsellors called justizrath, hofrath, etatsrath, educationsrath, comerzienrath, legationsrath, conferenzrath, or geheimerath, &c., who have never given any advice, or have been asked for by the king or his ministers. The majority of these titles and orders can be bought at a fixed price, and form a part of the revenue of the crown, like imports and exports of sugar and coffee, &c., in our custom houses. The government, glad to find fools enough to spend their money for banbles and toys, grants, graciously, the most humble request of these fools, and ridicules secretly these poor monkeys, an expression which I heard often from the then prince royal, now king of Denmark.

In spite of this general mania of titles, my father was one of the few, (among whom was also count Louis Reventlow,) who never applied neither for orders or titles. e was busily engaged to render his numerous peasantry as happy as possible, and was the first in the whole kingdom who gave them freedom and liberty; they were formerly slaves. But his greatest care was to give us a good, sound, and liberal education.

Ursula Acosta refererer hans fødselsregistrering fra Schwedt:5

Den 23. september 72 blev født i Schwedt kl. 8 om morgenen Henri Louis, søn af Pierre Villaume, præst i den franske kirke i Schwedt, og hans hustru Susanne, født Marre. Han blev hjemmedøbt den 8. oktober af sin far, båret af hans Kgl. Højhed markgreve Friedrich Heinrich von Schwedt und Wegern for hendes Kgl. højhed prinsesse Louise af Anhalt Dessau, født af Preussen.

Underskrevet: Villaume, præst

Friedrich Heinrich, prins af Preussen, markgrave af Schwedt (* 21 august 1709 i Schwedt, † 12 december 1788 i Schwedt) var den sidste ejer af det preussiske Sekundogenitur Schwedt-Wildenbruch.

Da hans bror Friedrich Wilhelm døde i 1771, arvede han herredømmet over Schwedt-Wildenbruch. Som markgrave af Brandenburg-Schwedt var han var en fortaler for kunst, især teater.

Luise af Brandenburg-Schwedt

L(o)uise Henriette Wilhelmine von Brandenburg-Schwedt (* 24. September 1750 i Stolzenberg, nu Rózanki /Polen; † 21. December 1811 i Dessau ) var gennem sit ægteskab prinsesse og senere hertuginde af Anhalt-Dessau.

Steven H. Smith refererer på the Napoleon Series:

“Villaume, citoyen danois, qui a deux frères dans les armées de la République, est autorisé à prendre du service; il se rendra au 4e batallion de la Sarthe commandé provisoirement par son frère.”

“Le sieur Willaume-Ducoudray, officier d'état-major à l'armée de Catalogne, est suspendu de ses fonctions; il sera arrêté et amené à Paris, et ses papiers seront saisis et envoyés en même temps au ministère de la police.”

“Villaume, citoyen danois, qui a deux frères dans les armées de la République, est autorisé à prendre du service; il se rendra au 4e batallion de la Sarthe commandé provisoirement par son frère.”

“Le sieur Willaume-Ducoudray, officier d'état-major à l'armée de Catalogne, est suspendu de ses fonctions; il sera arrêté et amené à Paris, et ses papiers seront saisis et envoyés en même temps au ministère de la police.”

Ducoudray skriver selv om La Fayette:6

In December 1795, I was at Hamburg at the house of Captain d'Archenholtz. He spoke to me, with great warmth and feeling, respecting the melancholy situation of the prisoners, and asked me if I was inclined to do any thing to assist them. I eagerly embraced the proposal, and told him that no consideration should restrain me, and that I was ready to make every attempt to release them from their barbarous imprisonment.

Messrs. John Parish, Archenholtz and Masson, in their frequent consultations together, watched with great zeal and solicitude the tortuous progress of the secret negotiations of the English and French diplomatists, to see when La Fayette and his companions became the subject of discussion. These three gentlemen were very well acquainted with several members of the British Parliament, and with persons initiated into the mysteries of the quintuple cabinet of the Luxembourg at Paris. But their inquiries left them not the smallest shadow of hope. Promises had been frequently made, but made only to be violated. These three gentlemen then admitted several others into their views, and it was resolved to despatch secretly an agent to Olmutz, to ascertain precisely the situation of the prisoners, and to inform them of the intentions their friends, in order to act with more prospect of success, and, if possible, to effect their escape from confinement. But the difficulty was, to find a person of confidence and courage, probity and prudence enough to qualify him for a mission so important. It was necessary, besides, that he should be able to speak German perfectly well, in order to avoid all possible suspicion.

Several persons were successively proposed, but there was always found something to object to; and the parties agreed to use their separate efforts to find the man who possessed the requisite qualifications.

The conversation which passed between d’Archenholtz and myself instantaneously suggested to his mind that I was the man they wanted. As he knew me thoroughly, he could easily vouch for my fitness and fidelity. I obtained the suffrages of all, and immediately prepared to set out. As I had already procured a furlough on account of my health, and as I was engaged in the service of the republic, rather as a volunteer than as lieutenant colonel with pay, I knew that I could easily obtain an extension of the term from the minister of war. I wrote accordingly, and left the arrangement of this business to my friends at Paris, telling them that family affairs of great urgency, would probably detain me a longer time in Holstein than I myself desired.

I had then several very long conferences with Messrs. D’Archenholtz, Masson and Sieveking. Having provided myself with a large packet of important despatches, money, bills of exchange, and letters of credit, to the amount of 200,000 Austrian florins, I set out from Hamburg in March, 1796. I had purchased a very elegant berlin, and my servant was faithful, clever, and discreet. My carriage was full of secret places, in which I concealed my numerous papers, my gold, my bills of exchange, and letters of credit, and John, who had served me from an early age, was initiated into all these mysteries, in order that he might be able to assist me in case of necessity.

But it was essentially requisite for me to change my costume and my name, because mine was too generally known throughout Germany. Sieveking and Archenholtz advised me to pass for a Swede, to assume another name and a title. They thought, that with these precautions, with a thorough knowledge of German, and something of Swedish, I would be able to extricate myself from any occasional dilemma. Captain d’Archenholtz took me the next day to the house of his friend, the Baron de Nordensköldt, secretary of the Swedish legation. After speaking a few words in private, which, Archenholtz afterwards told me, related to my pretended business in Austria and Silesia, the Baron asked me to leave my name, place of birth, age, &c., and added, that he would prepare my passport in the course of that day, and send it to me, signed by Mr. Claas Peyron, the Swedish Minister, who was at that time at Hamburg. I had previously selected my fictitious name, and was accordingly metamorphosed into a Swedish merchant, of the name of Peter Feldmann.

I armed myself and my servant with sabres, pistols and dirks, and took leave of my friends after settling upon a plan of secret correspondence, with an entire change of names. I travelled night and day, as my instructions and the information of which I was the bearer, were of the utmost importance to the prisoners. I thus passed rapidly through Leipsic, Dresden, Bautzen, to the frontiers of Bohemia, where the Austrian custom houses were situated, on a high mountain, in a little village called Peterswald. I arrived at this place about 8 A. M. and was obliged to submit to a very strict search; the keys were then demanded of my trunk, which was strapped and chained fast to the carriage. I handed them to John, and was about composing myself to sleep, being excessively fatigued, when I was roused by a dispute between my servant and the officers, about some meat and chocolate, which they declared to be prohibited, while my servant, who was a German, contradicted them stoutly. I soon settled the dispute by a present of a few florins to the principal officer, stating that the chocolate was medicated, by order of my physician, for my own use. My money had the desired effect; for no sooner did he see the siebzehners (Austrian coins, each of the value of two thirds of a florin, as near as I remember) in his own hand, than he ordered all things to he replaced, and very respectfully wished me a pleasant journey.

I was at last successful at the hotel Römische Kayser the landlord of which met me at the door and making me several low and obsequious bows called me your Excellency and Monsieur le Baron. His servility disgusted me and I told him I was neither an Excellency nor a Baron. He then saluted me with the title of Ihre Gnaden (your Lordship or your Grace) until to get rid of his fulsome compliments I asked him abruptly what paper he had in his hands. After a thousand ridiculous contortions and grimaces I was allowed to understand that it contained a list of questions printed by the order of police similar to the inquisitorial interrogatories which had already been put to me by the officer of the guard. At this I could scarcely control my impatience and found it difficult to summon sufficient self command to write the answers and sign the paper. The landlord then told me that if he unfortunately omitted to send to the police an hour after the arrival of a stranger at his hotel a paper filled up and signed like the one he had presented to me he would be punished by a fine of a thousand florins or by an imprisonment for 18 days.

Exhausted as I was with fatigue having travelled day and night from Hamburg without scarcely a moment's repose I was nevertheless so impatient to reach Olmutz that my intention was to remain at Prague only long enough to go to the banker's and procure the amount of a bill drawn at sight by Mr Strasow a banker at Hamburg. The letters of Sieveking were merely small slips of paper scarcely two fingers in breadth for after the failure of Bollmann no one was willing to incur the smallest unnecessary risk. On this account Sieveking advised me to conceal them with the utmost care which I accordingly did. As his handwriting could not be mistaken he did not sign any of these notes and they contained simply these words: “The bearer is my intimate friend; assist him in every thing as you would me.” The words in every thing which were underscored authorized me to draw for 50,000 florins in case of necessity as Mr Sieveking explained to me himself. But I was already too well provided to make use of his letter of credit.

This scrap of paper from Sieveking produced a wonderful effect. As soon as the Baron de Balabene had read it he received me with open arms begged me to tell him what service he could render me and paid me at once the amount of the bill of Strasow in such coin as I preferred; notwithstanding it was the day of the great festival I thought it prudent however not to communicate my intentions to him not from mistrust for Sieveking had recommended him as a man on whom I could entirely depend but as he could not in any way assist my designs it seemed unadvisable to make an unnecessary confidant.

The three prisoners of Olmutz owe their liberation exclusively to the esteem and regard in which they were held by Napoleon Bonaparte, at that time General in Chief of the army of Italy. The Directory had made very feeble efforts indeed, to effect their restoration to liberty, and that for reasons already assigned. But Bonaparte, by the advice of Major General Berthier, who highly esteemed La Fayette, resolutely insisted at the treaty of Campo Formio, which was preceded by the negotiation of Léoben and Udine, that, as an indispensable preliminary, the prisoners of Olmutz should be immediately released from confinement.

On arriving at Hamburg, Messrs. Parish, Morris, and a great number of other distinguished Americans, gave us a very splendid and magnificent entertainment on board of an elegant American ship, which lay at anchor in the harbour of the town. These gentlemen had previously sent several large barges, superbly decorated and manned with American seamen, to meet us at Haarburg, a town on the left bank of the Elbe, immediately opposite to Hamburg.

Through the attention of Messrs. Parish, Masson, Archenholtz, Sieveking, &c. lodgings had been secured and prepared for us all; and the next day M. Reinhardt, the French minister, gave us an elegant entertainment, at which the prisoners made their appearance with the tri-coloured cockade, which they had mounted on the day of their arrival on the territory of Hamburg, in order to show that they were not emigrants, nor indeed, had ever ceased to be Frenchmen and patriots.

It was here I enjoyed the pleasure of embracing my respected father, who had hastened to meet me, and to pay his tribute of respect to the illustrious prisoners. I had sent, when at Dresden, my servant with letters of invitation from these gentlemen, and from Madame de la Fayette, and entreating him to participate in the happiness of his son, who was now received into the bosom of their family.

Fra en samtidig anmeldelse i "The North American Review" af Edward Everett:7

The work published by General Ducoudray Holstein at New York is much worse. It is not entitled to credit. Nearly half of it is taken up with the five years that elapsed between the moment when General Lafayette left the army in August 1792 and his release from the dungeons of Olmutz in August 1797; and the whole of this when compared with the accounts given by Toulongeon, which Madame de Stael declares to be authentic; with Bollmann's own story of his attempt to rescue Lafayette in 1794; and with the general facts known everywhere and the details that may still be obtained from living witnesses can be considered only as an unhappy attempt at romance. Indeed the entire work is not much better for though in some portions the facts and dates may be given with more accuracy yet a false or exaggerated coloring is everywhere perceptible and the documents and public acts which were originally in English and after being translated into French by the author are now retranslated into English for his publisher come to us so travestied that their original features can hardly be recognised.

In December 1795, I was at Hamburg at the house of Captain d'Archenholtz. He spoke to me, with great warmth and feeling, respecting the melancholy situation of the prisoners, and asked me if I was inclined to do any thing to assist them. I eagerly embraced the proposal, and told him that no consideration should restrain me, and that I was ready to make every attempt to release them from their barbarous imprisonment.

Messrs. John Parish, Archenholtz and Masson, in their frequent consultations together, watched with great zeal and solicitude the tortuous progress of the secret negotiations of the English and French diplomatists, to see when La Fayette and his companions became the subject of discussion. These three gentlemen were very well acquainted with several members of the British Parliament, and with persons initiated into the mysteries of the quintuple cabinet of the Luxembourg at Paris. But their inquiries left them not the smallest shadow of hope. Promises had been frequently made, but made only to be violated. These three gentlemen then admitted several others into their views, and it was resolved to despatch secretly an agent to Olmutz, to ascertain precisely the situation of the prisoners, and to inform them of the intentions their friends, in order to act with more prospect of success, and, if possible, to effect their escape from confinement. But the difficulty was, to find a person of confidence and courage, probity and prudence enough to qualify him for a mission so important. It was necessary, besides, that he should be able to speak German perfectly well, in order to avoid all possible suspicion.

Several persons were successively proposed, but there was always found something to object to; and the parties agreed to use their separate efforts to find the man who possessed the requisite qualifications.

The conversation which passed between d’Archenholtz and myself instantaneously suggested to his mind that I was the man they wanted. As he knew me thoroughly, he could easily vouch for my fitness and fidelity. I obtained the suffrages of all, and immediately prepared to set out. As I had already procured a furlough on account of my health, and as I was engaged in the service of the republic, rather as a volunteer than as lieutenant colonel with pay, I knew that I could easily obtain an extension of the term from the minister of war. I wrote accordingly, and left the arrangement of this business to my friends at Paris, telling them that family affairs of great urgency, would probably detain me a longer time in Holstein than I myself desired.

I had then several very long conferences with Messrs. D’Archenholtz, Masson and Sieveking. Having provided myself with a large packet of important despatches, money, bills of exchange, and letters of credit, to the amount of 200,000 Austrian florins, I set out from Hamburg in March, 1796. I had purchased a very elegant berlin, and my servant was faithful, clever, and discreet. My carriage was full of secret places, in which I concealed my numerous papers, my gold, my bills of exchange, and letters of credit, and John, who had served me from an early age, was initiated into all these mysteries, in order that he might be able to assist me in case of necessity.

But it was essentially requisite for me to change my costume and my name, because mine was too generally known throughout Germany. Sieveking and Archenholtz advised me to pass for a Swede, to assume another name and a title. They thought, that with these precautions, with a thorough knowledge of German, and something of Swedish, I would be able to extricate myself from any occasional dilemma. Captain d’Archenholtz took me the next day to the house of his friend, the Baron de Nordensköldt, secretary of the Swedish legation. After speaking a few words in private, which, Archenholtz afterwards told me, related to my pretended business in Austria and Silesia, the Baron asked me to leave my name, place of birth, age, &c., and added, that he would prepare my passport in the course of that day, and send it to me, signed by Mr. Claas Peyron, the Swedish Minister, who was at that time at Hamburg. I had previously selected my fictitious name, and was accordingly metamorphosed into a Swedish merchant, of the name of Peter Feldmann.

I armed myself and my servant with sabres, pistols and dirks, and took leave of my friends after settling upon a plan of secret correspondence, with an entire change of names. I travelled night and day, as my instructions and the information of which I was the bearer, were of the utmost importance to the prisoners. I thus passed rapidly through Leipsic, Dresden, Bautzen, to the frontiers of Bohemia, where the Austrian custom houses were situated, on a high mountain, in a little village called Peterswald. I arrived at this place about 8 A. M. and was obliged to submit to a very strict search; the keys were then demanded of my trunk, which was strapped and chained fast to the carriage. I handed them to John, and was about composing myself to sleep, being excessively fatigued, when I was roused by a dispute between my servant and the officers, about some meat and chocolate, which they declared to be prohibited, while my servant, who was a German, contradicted them stoutly. I soon settled the dispute by a present of a few florins to the principal officer, stating that the chocolate was medicated, by order of my physician, for my own use. My money had the desired effect; for no sooner did he see the siebzehners (Austrian coins, each of the value of two thirds of a florin, as near as I remember) in his own hand, than he ordered all things to he replaced, and very respectfully wished me a pleasant journey.

I was at last successful at the hotel Römische Kayser the landlord of which met me at the door and making me several low and obsequious bows called me your Excellency and Monsieur le Baron. His servility disgusted me and I told him I was neither an Excellency nor a Baron. He then saluted me with the title of Ihre Gnaden (your Lordship or your Grace) until to get rid of his fulsome compliments I asked him abruptly what paper he had in his hands. After a thousand ridiculous contortions and grimaces I was allowed to understand that it contained a list of questions printed by the order of police similar to the inquisitorial interrogatories which had already been put to me by the officer of the guard. At this I could scarcely control my impatience and found it difficult to summon sufficient self command to write the answers and sign the paper. The landlord then told me that if he unfortunately omitted to send to the police an hour after the arrival of a stranger at his hotel a paper filled up and signed like the one he had presented to me he would be punished by a fine of a thousand florins or by an imprisonment for 18 days.

Exhausted as I was with fatigue having travelled day and night from Hamburg without scarcely a moment's repose I was nevertheless so impatient to reach Olmutz that my intention was to remain at Prague only long enough to go to the banker's and procure the amount of a bill drawn at sight by Mr Strasow a banker at Hamburg. The letters of Sieveking were merely small slips of paper scarcely two fingers in breadth for after the failure of Bollmann no one was willing to incur the smallest unnecessary risk. On this account Sieveking advised me to conceal them with the utmost care which I accordingly did. As his handwriting could not be mistaken he did not sign any of these notes and they contained simply these words: “The bearer is my intimate friend; assist him in every thing as you would me.” The words in every thing which were underscored authorized me to draw for 50,000 florins in case of necessity as Mr Sieveking explained to me himself. But I was already too well provided to make use of his letter of credit.

This scrap of paper from Sieveking produced a wonderful effect. As soon as the Baron de Balabene had read it he received me with open arms begged me to tell him what service he could render me and paid me at once the amount of the bill of Strasow in such coin as I preferred; notwithstanding it was the day of the great festival I thought it prudent however not to communicate my intentions to him not from mistrust for Sieveking had recommended him as a man on whom I could entirely depend but as he could not in any way assist my designs it seemed unadvisable to make an unnecessary confidant.

The three prisoners of Olmutz owe their liberation exclusively to the esteem and regard in which they were held by Napoleon Bonaparte, at that time General in Chief of the army of Italy. The Directory had made very feeble efforts indeed, to effect their restoration to liberty, and that for reasons already assigned. But Bonaparte, by the advice of Major General Berthier, who highly esteemed La Fayette, resolutely insisted at the treaty of Campo Formio, which was preceded by the negotiation of Léoben and Udine, that, as an indispensable preliminary, the prisoners of Olmutz should be immediately released from confinement.

On arriving at Hamburg, Messrs. Parish, Morris, and a great number of other distinguished Americans, gave us a very splendid and magnificent entertainment on board of an elegant American ship, which lay at anchor in the harbour of the town. These gentlemen had previously sent several large barges, superbly decorated and manned with American seamen, to meet us at Haarburg, a town on the left bank of the Elbe, immediately opposite to Hamburg.

Through the attention of Messrs. Parish, Masson, Archenholtz, Sieveking, &c. lodgings had been secured and prepared for us all; and the next day M. Reinhardt, the French minister, gave us an elegant entertainment, at which the prisoners made their appearance with the tri-coloured cockade, which they had mounted on the day of their arrival on the territory of Hamburg, in order to show that they were not emigrants, nor indeed, had ever ceased to be Frenchmen and patriots.

It was here I enjoyed the pleasure of embracing my respected father, who had hastened to meet me, and to pay his tribute of respect to the illustrious prisoners. I had sent, when at Dresden, my servant with letters of invitation from these gentlemen, and from Madame de la Fayette, and entreating him to participate in the happiness of his son, who was now received into the bosom of their family.

Fra en samtidig anmeldelse i "The North American Review" af Edward Everett:7

The work published by General Ducoudray Holstein at New York is much worse. It is not entitled to credit. Nearly half of it is taken up with the five years that elapsed between the moment when General Lafayette left the army in August 1792 and his release from the dungeons of Olmutz in August 1797; and the whole of this when compared with the accounts given by Toulongeon, which Madame de Stael declares to be authentic; with Bollmann's own story of his attempt to rescue Lafayette in 1794; and with the general facts known everywhere and the details that may still be obtained from living witnesses can be considered only as an unhappy attempt at romance. Indeed the entire work is not much better for though in some portions the facts and dates may be given with more accuracy yet a false or exaggerated coloring is everywhere perceptible and the documents and public acts which were originally in English and after being translated into French by the author are now retranslated into English for his publisher come to us so travestied that their original features can hardly be recognised.

Ducoudray fortæller om sit møde med Schiller8:

Jeg gjorde denne store mands bekendtskab på en meget særlig måde. Her er enkelthederne. Jeg befandt mig i 1803 i Bad Lauchstädt i Sachsen, som er meget populær i hele verden. Mange af disse udlændinge blev trukket til af Storhertugen af Weimars skuespillertrup, der var godt sammensat og stort. Det var dannet og udvalgt af Goethe og Schiller og blev med rette anses for at være i første klasse blandt de daværende tyske trupper, især i tragedien. Da jeg spadserede i en af alleerne omkring Bad Lauchstädt på den dag, jeg ankom, blev jeg meget overrasket over at høre mit navn kaldt af frk. Jag***, som var en berømt skuespillerinde i Weimar, som jeg havde set ofte ved hoffet hos storhertug Karl August, en af de mest oplyste og liberale herskere på sin tid. En dag havde jeg befundet mig i denne skuespillerindes salon, da døren pludselig åbnedes, og en slank og temmelig høj mand, med en fornem mine og en bleg hudfarve, med ørnenæse, præsenterede sig for os. Den unge skuespillerinde rejste sig og løb med åbne arme hen til den fremmede, som hun omfavnede med alle de følelser, som en ung pige havde, når hun genså sin far efter et langt fravær. Det var Schiller. Hun introducerede mig, og vi gjorde hurtigt hinandens bekendskab. Han sagde, at han havde hørt om mig gennem, hvad man sagde om mig i Weimar, hvor jeg opholdt mig i flere måneder.

Jeg gjorde denne store mands bekendtskab på en meget særlig måde. Her er enkelthederne. Jeg befandt mig i 1803 i Bad Lauchstädt i Sachsen, som er meget populær i hele verden. Mange af disse udlændinge blev trukket til af Storhertugen af Weimars skuespillertrup, der var godt sammensat og stort. Det var dannet og udvalgt af Goethe og Schiller og blev med rette anses for at være i første klasse blandt de daværende tyske trupper, især i tragedien. Da jeg spadserede i en af alleerne omkring Bad Lauchstädt på den dag, jeg ankom, blev jeg meget overrasket over at høre mit navn kaldt af frk. Jag***, som var en berømt skuespillerinde i Weimar, som jeg havde set ofte ved hoffet hos storhertug Karl August, en af de mest oplyste og liberale herskere på sin tid. En dag havde jeg befundet mig i denne skuespillerindes salon, da døren pludselig åbnedes, og en slank og temmelig høj mand, med en fornem mine og en bleg hudfarve, med ørnenæse, præsenterede sig for os. Den unge skuespillerinde rejste sig og løb med åbne arme hen til den fremmede, som hun omfavnede med alle de følelser, som en ung pige havde, når hun genså sin far efter et langt fravær. Det var Schiller. Hun introducerede mig, og vi gjorde hurtigt hinandens bekendskab. Han sagde, at han havde hørt om mig gennem, hvad man sagde om mig i Weimar, hvor jeg opholdt mig i flere måneder.

Ducoudray fortæller om sin deltagelse med Macdonald i slaget ved Wagram 18098:

"Da Bonaparte var blevet førstekonsul, sendte han general Macdonald som ambassadør til hoffet i Danmark. Da Moreau blev retsforfulgt og dømt, kunne Macdonald, der vendte hjem fra sin mission, ikke undlade at ytre sin utilfredshed med hele denne sag mod sin gamle general og ven. Førstekonsulen blev underrettet, og Macdonald havde ingen kommando i lang tid. Jeg har ofte oplevet ham spadsere på Paris’ boulevarder, meget enkelt klædt og i civil, med paraplyen under én arm og en af hans døtre under den anden. Han traf kun på daværende tidspunkt meget få mennesker og beskæftigede sig kun med undervisning af hans to børn, der havde haft den ulykke at miste deres mor. Hans mange venner formåede ikke at vinde nåde for ham hos førstekonsulen, og han forblev længe uden kommando.

Til sidst blev han sendt til Italien for at hjælpe vicekongen med at reorganisere denne hær og med at lede militære operationer. Krigen med Østrig brød ud noget senere. Med ønsket om at gense vicekongen og nysgerrig efter at se hans unge kone og hans hof, dengang meget lysere og mere muntert, bad jeg kejseren om at sende mig til Milano, som attaché ved dette hærkorps’ generalstab; denne tilladelse fik jeg uden vanskelighed.

Slaget ved Wagram er velkendt; her følger noget, som ikke er. General Macdonald, som jeg havde kendt godt tidligere, ønskede at jeg var sammen med ham under slaget. Han udmærker sig ved sin store koldblodighed og sine kloge dispositioner, og bidrog uden tvivl hjulpet af den tillid, som hans kammerater havde til ham, meget til succesen på denne blodige og strålende dag. Han havde to heste dræbt under ham, og af mere end tyve generalstabsofficerer forblev kun syv i stand til at gøre tjeneste; resten blev dræbt eller såret. Hver af os mistede en eller flere heste, fordi vi blev udsat mere end en times beskydning af den mest formidable størrelse fra et batteri, der var etableret på et plateau midt på sletten. Hæren i Italien mødte der en beskydning, der var så dødbringende, at af f. eks. en infanteri regiment på mere end 1.200 mænd, forblev knap hundrede i stand til at gøre tjeneste; allle andre blev dræbt eller såret. Dette batteri blev endeligt fjernet ved beskydning, hvilket afgjorde sejren, denne katastrofale sejr, som fordrejede hovedet på Napoleon, så han mente at kunne tillade sig alt. Han forskød Joséphine, hans enestående veninde, hun som havde bidraget så virksomt til hans storhed, og ofrede hende for at gå forene sig med en østriger, hvis hus gennem århundreder har været den uforsonlige fjende af Frankrig! Fra denne dag faldt Napoleon stjerne, fra denne dag kunne adskillige velunderrettede og fremsynede mennesker forudsige hans fald, eller i det mindste nogle af de ulykker, der blev nationens, og som kostede hundredtusind mænds liv!

Slaget blev vundet; under slaget blev general Macdonald såret i benet; og da han alligevel forblev til hest, indtil sagen var besluttet, var hans ben så betændt, at man måtte skære støvlen af ham. Vi flyttede ham til en hytte i nærheden, og de få generalstabsofficerer, der blev der, var så trætte, at de kun med vanskelighed var i stand til at behandle de sårede, som var stuvet sammen i denne elendige hytte. Pludselig hørte vi udefra en høj stemme, der råbte, Macdonald, Macdonald, hvor er du dog? Det var general Rapp, der blev beordret til at gå ud og søge efter ham og bringe ham til kejserens hovedkvarter. Da general Macdonalds sår kun var let, var han i stand til at ride, og vi fulgte ham meget nysgerrige efter at vide, hvad kejseren ville ham. Sidstnævnte, omgivet af et stort følge ventede på hesteryg ved indgangen til landsbyen, som general Rapp havde sagt. Så snart Napoleon så Macdonald, pressede han sin hest, kastede sig over den sårede general og omfavnede ham med kyssede en sådan kraft, at Macdonald (som han fortalte mig kort efter) næsten faldt af hesten. Han fortalte ham foran alle i en meget høj og klar tonet: General Macdonald, lad os glemme fortiden, lad os være venner, jeg gør Dem til marskal og hertug, det har de fortjent. Siden da forblev Macdonald tæt knyttet til ham lige indtil hans abdikation. "

"Da Bonaparte var blevet førstekonsul, sendte han general Macdonald som ambassadør til hoffet i Danmark. Da Moreau blev retsforfulgt og dømt, kunne Macdonald, der vendte hjem fra sin mission, ikke undlade at ytre sin utilfredshed med hele denne sag mod sin gamle general og ven. Førstekonsulen blev underrettet, og Macdonald havde ingen kommando i lang tid. Jeg har ofte oplevet ham spadsere på Paris’ boulevarder, meget enkelt klædt og i civil, med paraplyen under én arm og en af hans døtre under den anden. Han traf kun på daværende tidspunkt meget få mennesker og beskæftigede sig kun med undervisning af hans to børn, der havde haft den ulykke at miste deres mor. Hans mange venner formåede ikke at vinde nåde for ham hos førstekonsulen, og han forblev længe uden kommando.

Til sidst blev han sendt til Italien for at hjælpe vicekongen med at reorganisere denne hær og med at lede militære operationer. Krigen med Østrig brød ud noget senere. Med ønsket om at gense vicekongen og nysgerrig efter at se hans unge kone og hans hof, dengang meget lysere og mere muntert, bad jeg kejseren om at sende mig til Milano, som attaché ved dette hærkorps’ generalstab; denne tilladelse fik jeg uden vanskelighed.

Slaget ved Wagram er velkendt; her følger noget, som ikke er. General Macdonald, som jeg havde kendt godt tidligere, ønskede at jeg var sammen med ham under slaget. Han udmærker sig ved sin store koldblodighed og sine kloge dispositioner, og bidrog uden tvivl hjulpet af den tillid, som hans kammerater havde til ham, meget til succesen på denne blodige og strålende dag. Han havde to heste dræbt under ham, og af mere end tyve generalstabsofficerer forblev kun syv i stand til at gøre tjeneste; resten blev dræbt eller såret. Hver af os mistede en eller flere heste, fordi vi blev udsat mere end en times beskydning af den mest formidable størrelse fra et batteri, der var etableret på et plateau midt på sletten. Hæren i Italien mødte der en beskydning, der var så dødbringende, at af f. eks. en infanteri regiment på mere end 1.200 mænd, forblev knap hundrede i stand til at gøre tjeneste; allle andre blev dræbt eller såret. Dette batteri blev endeligt fjernet ved beskydning, hvilket afgjorde sejren, denne katastrofale sejr, som fordrejede hovedet på Napoleon, så han mente at kunne tillade sig alt. Han forskød Joséphine, hans enestående veninde, hun som havde bidraget så virksomt til hans storhed, og ofrede hende for at gå forene sig med en østriger, hvis hus gennem århundreder har været den uforsonlige fjende af Frankrig! Fra denne dag faldt Napoleon stjerne, fra denne dag kunne adskillige velunderrettede og fremsynede mennesker forudsige hans fald, eller i det mindste nogle af de ulykker, der blev nationens, og som kostede hundredtusind mænds liv!

Slaget blev vundet; under slaget blev general Macdonald såret i benet; og da han alligevel forblev til hest, indtil sagen var besluttet, var hans ben så betændt, at man måtte skære støvlen af ham. Vi flyttede ham til en hytte i nærheden, og de få generalstabsofficerer, der blev der, var så trætte, at de kun med vanskelighed var i stand til at behandle de sårede, som var stuvet sammen i denne elendige hytte. Pludselig hørte vi udefra en høj stemme, der råbte, Macdonald, Macdonald, hvor er du dog? Det var general Rapp, der blev beordret til at gå ud og søge efter ham og bringe ham til kejserens hovedkvarter. Da general Macdonalds sår kun var let, var han i stand til at ride, og vi fulgte ham meget nysgerrige efter at vide, hvad kejseren ville ham. Sidstnævnte, omgivet af et stort følge ventede på hesteryg ved indgangen til landsbyen, som general Rapp havde sagt. Så snart Napoleon så Macdonald, pressede han sin hest, kastede sig over den sårede general og omfavnede ham med kyssede en sådan kraft, at Macdonald (som han fortalte mig kort efter) næsten faldt af hesten. Han fortalte ham foran alle i en meget høj og klar tonet: General Macdonald, lad os glemme fortiden, lad os være venner, jeg gør Dem til marskal og hertug, det har de fortjent. Siden da forblev Macdonald tæt knyttet til ham lige indtil hans abdikation. "

Fra "Efterladte papirer fra den Reventlowske familiekreds":9

Tr. den 28. marts 1812.

I går kom Dencker retur fra Himmelmark med et meget interessant brev til os - ankommet som ved et mirakel. Villaumes søn i Spanien havde ikke givet livstegn fra sig siden maj, han havde været kommandant over citadellet i Barcelona. I august ankom en ordre, underskrevet af selveste N. om at arrestere ham, beslaglægge hans papirer og bringe ham under god eskorte som fange til Paris, uden at begrunde en sådan vold, eller at hans overordnede havde klaget over ham. Han mødte en stor interesse hos alle sine kammerater. Vreden gav ham en voldsom feber, han blev godt behandlet, uden særlig bevogtning, og kunne modtage besøg fra venner og veninder, når han ønskede, og fandt, mens han ventede, mulighed for at tilbyde sine tjenester til grev Lafey, general i spidsen for de spanske tropper i Catalonien, for at modtage hans svar og en angivelse af, hvor han kunne finde et godt kavalerikorps, som kunne føre ham sikkert til hovedkvarteret. Han reddede sig i november, og er nu aide-de-camp for Lassy og har bistået i to affærer mod franskmændene, hvor spanierne fik fordelen; de er fulde af entusiasme, siger han, og vil sikkert vinde sejren. Dette usignerede brev var adresseret til Schalburg i Eckernförde fra Hamburg, med 21 pd. 8 i porto, hvordan kunne det dog nå frem? Det blev påbegyndt i december og afsluttet den 20. feb.

Tr. den 28. marts 1812.

I går kom Dencker retur fra Himmelmark med et meget interessant brev til os - ankommet som ved et mirakel. Villaumes søn i Spanien havde ikke givet livstegn fra sig siden maj, han havde været kommandant over citadellet i Barcelona. I august ankom en ordre, underskrevet af selveste N. om at arrestere ham, beslaglægge hans papirer og bringe ham under god eskorte som fange til Paris, uden at begrunde en sådan vold, eller at hans overordnede havde klaget over ham. Han mødte en stor interesse hos alle sine kammerater. Vreden gav ham en voldsom feber, han blev godt behandlet, uden særlig bevogtning, og kunne modtage besøg fra venner og veninder, når han ønskede, og fandt, mens han ventede, mulighed for at tilbyde sine tjenester til grev Lafey, general i spidsen for de spanske tropper i Catalonien, for at modtage hans svar og en angivelse af, hvor han kunne finde et godt kavalerikorps, som kunne føre ham sikkert til hovedkvarteret. Han reddede sig i november, og er nu aide-de-camp for Lassy og har bistået i to affærer mod franskmændene, hvor spanierne fik fordelen; de er fulde af entusiasme, siger han, og vil sikkert vinde sejren. Dette usignerede brev var adresseret til Schalburg i Eckernförde fra Hamburg, med 21 pd. 8 i porto, hvordan kunne det dog nå frem? Det blev påbegyndt i december og afsluttet den 20. feb.

Ducoudray-Holstein i Louisiana 1813:

USA’s regering fulgte med interesse, at uafhængighedsbevægelser spredte sig ud over Spaniens kolonirige i Latinamerika.

Også i Mexico havde der været oprør, der blev nedkæmpet. Vinteren 1812 besøgte mexicaneren Bernardo Gutierrez Washington for at få hjælp. Den fik han gennem agenten William Shaler, der fulgte ham til byen Natchitoches, tæt på grænsen mellem USA (Louisiana) og Spanien (Texas). Her samlede han styrker til en invasion af Texas, de fleste var amerikanere, herunder løjtnant Augustus Magee, som trak sig fra USA’s hær for at være medkommandant på ekspeditionen, der er kendt som ”Magee Gutierrez Ekspeditionen”. Det fortælles, at eventyrere og fribyttere flokkedes til Natchitoches for at være med, en del for at vinde Texas for USA. Der skulle have været dristige amerikanere, utilfredse spaniere, udspekulerede franskmænd og pirater fra Jean Lafittes bande.

8. August 1812 krydsede Magee og Gutierrez Sabine floden ind i Spansk Texas med 130 mand. De vandt nogle slag, og amerikanere og mexicanere sluttede sig til for at vinde bytte, ivrigt opmuntert af de handlende i Natchitoches. De rykkede ind i San Antonio 1. april 1813, hvor de udråbte republikken Texas.

Det officielle USA modsatte sig ekspeditionen, men forhindrede den ikke. Det antages, at udenrigsminister James Monroe hemmeligt støttede ekspeditionen.

Oprøret begyndte hurtigt at udarte, den spanske guvernør og en del tilfangetagne officerer blev myrdet, og mange af amerikanerne trak sig. Shaler fik skiftet Gutierrez ud med en håndplukket efterfølger, Jose Alvarez de Toledo, men spanierne besejrede oprørerne 18. august 1813 i slaget ved San Medina.

Undervejs søgte den spanske ambassadør til USA, Luis de Onís, også at påvirke sagens gang. Sommeren 1813 hævdede han over for James Monroe, at Toledo havde en intrige gående med franskmændene om at afsætte Gutierrez og lade franskmændene overtage ekspeditionen. Han påstod herunder, at Ducoudray-Holstein og Bartholomé Lafon, som ankom til Rapides, Louisiana, juni 1813, var franske agenter, der konspirerede med Toledo. Rapides var kendt som et arnested for fransksindede i det Louisiana, som USA havde købt af Frankrig i 1803.

USA’s regering fulgte med interesse, at uafhængighedsbevægelser spredte sig ud over Spaniens kolonirige i Latinamerika.

Også i Mexico havde der været oprør, der blev nedkæmpet. Vinteren 1812 besøgte mexicaneren Bernardo Gutierrez Washington for at få hjælp. Den fik han gennem agenten William Shaler, der fulgte ham til byen Natchitoches, tæt på grænsen mellem USA (Louisiana) og Spanien (Texas). Her samlede han styrker til en invasion af Texas, de fleste var amerikanere, herunder løjtnant Augustus Magee, som trak sig fra USA’s hær for at være medkommandant på ekspeditionen, der er kendt som ”Magee Gutierrez Ekspeditionen”. Det fortælles, at eventyrere og fribyttere flokkedes til Natchitoches for at være med, en del for at vinde Texas for USA. Der skulle have været dristige amerikanere, utilfredse spaniere, udspekulerede franskmænd og pirater fra Jean Lafittes bande.

8. August 1812 krydsede Magee og Gutierrez Sabine floden ind i Spansk Texas med 130 mand. De vandt nogle slag, og amerikanere og mexicanere sluttede sig til for at vinde bytte, ivrigt opmuntert af de handlende i Natchitoches. De rykkede ind i San Antonio 1. april 1813, hvor de udråbte republikken Texas.

Det officielle USA modsatte sig ekspeditionen, men forhindrede den ikke. Det antages, at udenrigsminister James Monroe hemmeligt støttede ekspeditionen.

Oprøret begyndte hurtigt at udarte, den spanske guvernør og en del tilfangetagne officerer blev myrdet, og mange af amerikanerne trak sig. Shaler fik skiftet Gutierrez ud med en håndplukket efterfølger, Jose Alvarez de Toledo, men spanierne besejrede oprørerne 18. august 1813 i slaget ved San Medina.

Undervejs søgte den spanske ambassadør til USA, Luis de Onís, også at påvirke sagens gang. Sommeren 1813 hævdede han over for James Monroe, at Toledo havde en intrige gående med franskmændene om at afsætte Gutierrez og lade franskmændene overtage ekspeditionen. Han påstod herunder, at Ducoudray-Holstein og Bartholomé Lafon, som ankom til Rapides, Louisiana, juni 1813, var franske agenter, der konspirerede med Toledo. Rapides var kendt som et arnested for fransksindede i det Louisiana, som USA havde købt af Frankrig i 1803.

Tim Mahon beretter på the Napoleon Series:

Found the letter - the following translation is mine and is a little rough at this point. It may well be this is the wrong brother - still an interesting little insight into what went on outside the major events of the time, however.

General Ducoudray in the United States and Mexico (1812-1813)

Originally published in French as Ducoudray, J.-D.-V.: Le général Ducoudray aux États-Unis et au Mexique (1812-1813) in Nouvelle Revue Rétrospective, cinquième semestre (juillet-décembre 1896), Paris, 1896, pp. 140-143

Letter to M. Champigny-Aubin1

New Orleans, 17 December 1813

“I have been here in the capital of Louisiana, my dear Champigny, for a month, on the pleasant banks of the Mississippi and am taking advantage of a great opportunity to write you this letter and to let you know I am in good health, happy and rich.

Over the last two years I must have written to you at least fifteen times, but do not know whether you have received my epistles. At the risk of repeating myself, I must tell you that I left Cadiz on 24th November 1812 and disembarked at Norfolk, with a surgeon-major friend of mine named Lafon, on 4th February; that I passed via Baltimore to New York and Philadelphia, from whence I wrote to you twice; that there I was appointed adjudant-général in the service of the United States and finally a chief on the general staff and a général de brigade in the republican army of Mexico; that in March I left Philadelphia by land for Pittsburgh; that from there I wrote to you again to tell you that I was leaving by river along the Ohio and the Mississippi with 300 men and a number of good officers and, after a voyage of more than 700 leagues, I arrived on the Mexican frontier with my entourage, at Natchitotches on the Red River in the province of Texas. Look at a map and you will understand the situation.

On arriving in the month of July, I received the bad news that the patriots of this province had been utterly defeated by the royalists; that their general had so lost his head that he had abandoned everything and fled like a coward to the United States; and finally that the Republic of Texas, which had existed for more than two years, had been lost by the ineptitude of this General Toledo. He has been dismissed and is dishonoured for eternity.